Navigating Family Breakdown: Understanding the invisible burden students carry

In every Australian secondary classroom, 1 in 5 students is navigating family breakdown. This comprehensive guide equips educators with trauma-informed strategies to support these vulnerable students.

The Scale in Australia

Divorces in 2024

Involve children

Students affected

Identifying Students in Need

Look beyond the behavior. The bright student slipping, the quiet withdrawer, the reactive outburst—these may all be signals of deeper struggles.

Understanding the difference between truancy and school refusal is critical for appropriate intervention.

The Developing Brain

Adolescence is a critical period of neuroplasticity. The stress from family breakdown can overwhelm developing brains, leaving fewer resources for learning.

High-Risk Groups

Students aged 15-17 show the highest distress levels (21%). Students with special needs, particularly ASD, face compounded challenges.

Ages 15-17: Peak vulnerability period during secondary years

Trauma-Informed Strategies

Relationship

Build trust and connection

Stamina

Nurture resilience

Adjustments

Provide tailored support

Legal Considerations

Navigate complex family law situations while maintaining professional boundaries and student wellbeing.

- • Understanding AVOs and court orders

- • Managing communication with separated parents

- • Confidentiality and information sharing

Additional Resources

Access support services, professional reading, and crisis contacts for students and families.

"Heal first, then thrive."

While teachers cannot fix a broken home, they can build a classroom that remains whole, safe, and supportive.

Background & Prevalence

Understanding Family Breakdown in Australian Schools

Introduction: Beyond the "Single Event" Perception

Welcome to the first section of this professional learning resource. Before exploring specific teaching strategies, it's essential for secondary educators to develop an accurate understanding of "family breakdown" as a phenomenon. In Australian educational contexts, family breakdown is not merely a legal term—it is regarded as a prevalent and complex childhood adversity (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

"Family breakdown is not viewed as a single event, but as a prolonged process of family reorganisation that fundamentally alters a student's developmental environment" (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2020, p. 1).

This process often means students experience years of uncertainty during their critical developmental period of adolescence, affecting their capacity for learning and emotional regulation.

Legal Framework & Core Definitions

Family Law Act 1975

The cornerstone is Family Law Act 1975, establishing that all legal actions should ensure children receive appropriate and adequate parenting to help them achieve their full potential (NSW Government, 2021).

Focus: Child's best interests, not parental rights

Parental Responsibility

Unless court orders specify otherwise, the law presumes shared parental responsibility for major long-term decisions affecting the child (NSW Government, 2021).

- • Current education arrangements

- • Future educational planning

- • Religious and cultural upbringing

- • Health including mental health

The Reality Behind the Data: Scale in Australia

Divorces granted in 2024

(Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024)

Involve children under 18

(Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024)

The Hidden Scale

Official divorce statistics significantly underestimate the reality. When considering all forms of relationship breakdown, including de facto marriages and unregistered separations:

Children experience parental separation before age 18

(Halford, 2018, as cited in Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

The Critical Timeline: Why Secondary School Matters

The timeline dimension is crucial for secondary educators. The stress doesn't begin with the divorce decree nor end there—it spans years of uncertainty.

The 3-4 Year Gap

Marriage → Separation

9.3 years

Median duration

Separation → Divorce

3.9 years

Median duration

Implication: This 3-4 year lag often covers the critical secondary school period (Years 7-10), when students are already navigating adolescence while their families are in high-conflict legal disputes (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024).

Neurobiological Perspective: Why Family Conflict Changes the Brain

Adolescent Brain Vulnerability

Adolescence is a neurobiological vulnerability period when the prefrontal cortex (executive functions) and limbic system (emotions) are rebalancing (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Chronic exposure to high-conflict divorce triggers sustained cortisol secretion—biomarkers for depression and psychological dysfunction (Mannie et al., 2007, as cited in Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

fMRI Research Findings

Turpyn et al. (2017) found that when parents exhibit high negative emotion and poor regulation:

- • Amygdala: Heightened threat detection response

- • vmPFC: Over-activation for emotional regulation

- • Result: Reduced cognitive resources for learning

Peak Vulnerability: Ages 15-17

Contrary to common assumptions, older adolescents show the highest distress levels during family breakdown:

Report high distress during routine separations

(Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2020)

Professionals express concern for wellbeing

(Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2020)

This confirms that secondary school students face unique vulnerability during family breakdown, likely due to identity formation, peer relationship building, and increasing academic pressures occurring simultaneously with family instability.

School as "Safe Haven"

When home becomes "instability" and "unknown sadness," school is often the only place providing predictability, safety, consistency, and routine (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

First Responders

Daily contact enables early identification

Trust Building

Students confide when relationship-based

Emotional Buffer

Non-judgmental space for healing

Decoding the Signals

Identifying Adolescents in Crisis

The Challenge of Identification

For secondary educators, identifying a student struggling with family breakdown is often the first and most critical step in providing support. However, this task is fraught with complexity as adolescence is already a period of rapid developmental change, characterized by emotional volatility and a push for independence (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Consequently, the distress signals of family breakdown often blur with "typical" teenage behaviors, making them easy to miss or misinterpret (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025). This page equips educators with the discernment needed to distinguish between standard adolescent development and the specific red flags of family trauma.

The Complexity of Detection: "All-Encompassing Underlying Stress"

The Mask of Normality

Adolescents are often adept at masking their distress, driven by stigma or desire to protect parents (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025):

- • Withdrawal over Outreach: Students "avoid engaging" and try to "float through" instead of connecting

- • Misinterpretation: Moodiness and irritability dismissed as "just being a teenager"

Chronic, Not Acute Stress

HCD presents as a chronic, low-level hum of anxiety—an "all-encompassing kind of underlying stress" that is "bubbling underneath all the time" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

When home is "instability" and "constant unknown sadness," school must become the "safe haven" of predictability and reliability

The Core Warning Signal: School Refusal

Defining School Refusal vs. Truancy

School refusal is characterized by severe emotional distress at the prospect of attending school, fundamentally different from truancy (Clark, 2022).

| Feature | School Refusal (Distress Signal) | Truancy (Conduct Issue) |

|---|---|---|

| Root Cause | Severe emotional distress / Anxiety (Clark, 2022) | Lack of interest / Conduct disorder |

| Parental Knowledge | Parents know and try to enforce attendance (Clark, 2022) | Parents unaware; absences concealed |

| Student Mindset | Wants to attend but lacks emotional capacity (Clark, 2022) | Chooses not to attend |

| Link to Breakdown | Strongly linked to separation anxiety (Clark, 2022) | Linked to peer influence/disengagement |

The Continuum of Refusal Behaviors

Attends with significant distress, pleads to stay home

Morning misbehavior, psychosomatic complaints

Misses specific classes or days repeatedly

Absent for extended periods (weeks/months)

Early identification is critical - longer absences increase dropout risk (Clark, 2022)

Academic & Cognitive Indicators: The "Brain on Stress"

Chronic stress affects the prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like planning and focus (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025). Academic changes often reflect cognitive resource depletion.

Missed Deadlines

Students "get really stressed" about deadlines due to logistical chaos of living between houses (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Focus Issues

"Struggle to concentrate" - cognitive resources diverted to emotional regulation (Turpyn et al., 2017)

Declining Grades

Noticeable "marks drop" despite efforts to keep up (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

The Danger of Misinterpretation

These behaviors are physiological responses to stress, not laziness or defiance. Students are physiologically "primed to detect threats," incompatible with relaxed focus required for learning (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Emotional Expression: Internalizing vs. Externalizing

Internalizing Behaviors

Easily overlooked but signal profound distress:

- • Transition Anxiety: 21% of ages 15-17 show distress during routine separations (AIFS, 2020)

- • Friday Phenomenon: Heightened anxiety before custody transfers (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

- • Somatic Complaints: Stomach aches, headaches before school

Externalizing Behaviors

More disruptive but equally desperate cries for help:

- • Aggression/Defiance: Students may "exhibit some of the same behaviours as violent parents" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

- • Social Friction: Both patterns damage peer relationships, increasing isolation

When Family Violence is Present

↓

Lower child wellbeing (AIFS, 2020)

↓

Worse school performance (AIFS, 2020)

New violence after separation often has worse impact than violence during relationship

High-Risk Group: Students with Special Needs (ASD/ADHD)

The Disruption of Routine

Students with ASD rely on "predictable and fixed routines" and structure (Hetherington, 2017). Divorce dismantles this essential foundation.

Sensory Overload

Moving houses, changing schedules trigger severe anxiety and sensory overload (Hetherington, 2017)

Logistical Anxiety

Forgetting materials at "Dad's house" becomes a major crisis for students struggling with flexibility (Hetherington, 2017)

Systemic Barrier: "Communication Uncertainty"

Schools must provide "reasonable adjustments" (Page et al., 2024), but HCD creates barriers:

- • Decision Authority: Which parent approves IEPs or medical decisions?

- • Third-Party Complications: Stepparents/grandparents may lack legal consent for information sharing (NSW Government, 2021)

- • Delayed Support: Communication uncertainty delays critical adjustments (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

What Adolescents Want: The Student Voice

To Be Heard

Ages 10-17 want views "listened to by their parents" (AIFS, 2020). In school, this translates to agency in their own lives.

Safety First

When abuse is a concern, adolescents desperately want fears "heard and acted on" (AIFS, 2020)

Access to Support

Students express desire for "counsellors, psychologists, and support groups" (AIFS, 2020)

From "Annoyance" to Empathy

Identifying the signs of family breakdown requires shifting from reacting with "annoyance and frustration" to meeting students with "compassion" and professional insight (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

By recognizing that school refusal, academic decline, and "acting out" are physiological responses to chronic stress, schools can fulfill their role as a "safe haven" for vulnerable students.

The Neurobiology of Breakdown

How Adversity Reshapes Learning

Beyond Behavior to Biology

Family breakdown, particularly when characterized by high-conflict divorce, is not merely an emotional or social challenge for adolescents—it is a physiological event that can fundamentally alter neurobiological development and cognitive function (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025; Turpyn et al., 2017).

For educators, understanding the biological underpinnings of student behavior transforms the pedagogical lens from viewing disruptive or withdrawn behavior as a "choice" to recognizing it as a physiological response to chronic trauma (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

The Vulnerable Adolescent Brain: Plasticity and Imbalance

Adolescence is a critical period of neurobiological vulnerability, defined by high plasticity—the brain's ability to reshape itself in response to the environment (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Structural Remodeling

The Imbalance Model

Matures early (emotion, threat detection)

Still developing (executive functions)

This gap creates heightened emotional sensitivity with still-developing regulation capacity (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Chronic Stress & Cortisol

High-conflict family environments activate the stress response system chronically:

- • Cortisol Secretion: Sustained release of stress hormone

- • Neurobiological Marker: Linked to depression and psychological dysfunction (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

The student remains in high physiological arousal, significantly increasing poor psychosocial outcomes

The Cost to Executive Function: Why "Smart" Students Struggle

Chronic stress directly impacts the prefrontal cortex, the engine of academic success, explaining why capable students may suddenly struggle to learn.

Impulse Control Issues

Manifests as defiance or aggression, often mislabeled as disciplinary issues rather than regulatory failures (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Planning & Organization

Exacerbated by logistical chaos of dual households and schedule instability (Hetherington, 2017; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Inattention & Withdrawal

Cognitive resources deployed to manage emotional state, leaving little for classroom engagement (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Visible Academic Consequences

Declining Grades

Teachers report distinct "marks drop" as students struggle amidst cognitive load (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Deadline Anxiety

Students get "really stressed" about assignments when unexpectedly at the "other parent's house" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

School Refusal Driver: Long-term conflict is a key driver of school refusal, increasing dropout risk (Clark, 2022)

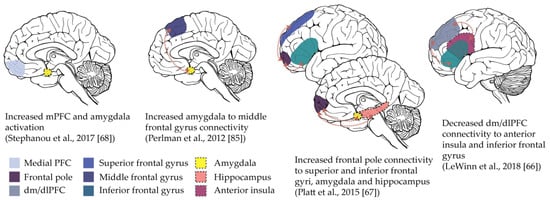

Neural Coupling: How Parents Shape the Teen Brain

fMRI research reveals a complex "neural coupling" between parent and child—parental emotional regulation ability plays a critical role in protecting or exacerbating adolescent vulnerability (Turpyn et al., 2017).

The Amygdala: Overactive Threat Detector

The brain's threat detection center processes emotion and triggers stress response:

- • Higher parental negative emotion → stronger adolescent amygdala response (Turpyn et al., 2017)

- • Transmission through genetic modeling or environmental exposure

- • Student's brain becomes "wired" to overreact to negativity

The vmPFC: Exhausted Regulator

Regulatory regions recruited to manage emotional conflict:

The Critical Moderator

Worst Case: High negative emotion + poor regulation

→ Maximum amygdala & vmPFC response (Turpyn et al., 2017)

→ Over-engagement depletes regulatory resources

Best Case: Good parent coping skills breaks stress transmission link

"Physiologically Prepared for Threat"

Adolescents may automatically deploy significant regulatory resources just to function. By entering the classroom, they're already experiencing resource depletion, leaving reduced capacity for learning (Orygen, 2025; Turpyn et al., 2017).

The Educational Challenge: Misinterpreting Trauma as Deficit

The damage to neurobiology and executive function creates a core challenge: distinguishing physiological trauma responses from inherent ability or attitude.

When a student fails to submit an assessment or withdraws from group work, teachers might assume the student lacks motivation. However, this is likely a student with a compromised prefrontal cortex, whose cognitive resources have been exhausted by family conflict, making complex planning physically difficult (Orygen, 2025; Turpyn et al., 2017).

The following illustration highlights the specific neural pathways most impacted by chronic family stress:

The Trauma-Informed Imperative

The impact of family breakdown is multi-layered, chronic, and physiological. Schools must adopt a trauma-informed lens, redefining withdrawal, anxiety, or aggression not as disciplinary problems but as signals that "all is not well in the young person's world" (Devenney & O'Toole, as cited in Clark, 2022).

"Only by understanding that family conflict is a neurobiological drain can schools provide effective support and truly serve as safe havens for vulnerable students."

The Berry Street Education Model (BSEM) prioritizes "healing first, then thriving" (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019), providing the framework for this trauma-informed approach.

The Double Burden

Supporting High-Risk and Vulnerable Students

Identifying Compounded Vulnerability

While parent reports suggest that the majority of children are perceived to be faring well after parental separation, this general statistic often masks the reality for specific subgroups who face compounded vulnerabilities (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2020).

The chronic stress inherent in family breakdown can severely exacerbate existing developmental challenges, leading to rapid academic disengagement and school refusal (Clark, 2022). This page focuses on recognizing these high-risk cohorts and addressing the systemic barriers that prevent them from receiving support.

Special Educational Needs

Students with ASD/ADHD facing compounded challenges during family transition

↓

Family Violence Exposure

Students exposed to violence face the highest risk for developmental regression

↓

Culturally Diverse

First Nations students and those facing intersectional disadvantage

↓

Enhanced Vulnerability: Students with Special Educational Needs

Students with ASD and ADHD face significantly higher risk of school refusal and disengagement following family disruption compared to neurotypical peers (Clark, 2022).

Chaos vs. Order

Children with autism require predictable and fixed routines for effective functioning (Hetherington, 2017).

- • Routine Destruction: Separation introduces instability and complexity

- • Transition Burden: Dual households create sensory overload and anxiety (Hetherington, 2017)

- • Logistical Crises: Forgotten materials trigger major anxiety (Hetherington, 2017)

Functional Behaviors

Distress manifests in behaviors that require careful interpretation:

Self-Stimulatory (Stimming)

Functional response to anxiety - serves emotional regulation purpose (Hetherington, 2017)

Sensory Seeking/Withdrawal

Managing sensory overload through coping mechanisms (Hetherington, 2017)

Critical: Do not punish coping mechanisms without providing alternatives (Hetherington, 2017)

Systemic Barriers: The Crisis of "Communication Uncertainty"

Legal Mandate vs. Practical Reality

Under Disability Standards for Education 2005, schools must make "reasonable adjustments" for students with disabilities (Page et al., 2024).

How Conflict Blocks Support

IEPs & Educational Plans

Struggle to get signatures or agreement on learning goals (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Medical Interventions

Approval for assessments stalled due to parental disagreement (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Third-Party Complications

Cannot share information with stepparents/grandparents without consent (NSW Government, 2021; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

IEPs & Educational Plans

Struggle to get signatures or agreement on learning goals (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Medical Interventions

Approval for assessments stalled due to parental disagreement (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Third-Party Complications

Cannot share information with stepparents/grandparents without consent (NSW Government, 2021; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

The Consequence: Educational Inequity

Private family dispute becomes systemic barrier to legal rights

The Shadow of Violence: Compounded Trauma

The risk of compromised wellbeing is significantly heightened when students are exposed to family violence or emotional abuse.

Prevalence & Impact

• Lower Wellbeing: Significantly reduced overall wellbeing (AIFS, 2020)

• Academic Decline: Worse performance in learning (AIFS, 2020)

• 71% Affected: Parents report child affected by witnessed violence (AIFS, 2020)

Critical Timing Factor

Key Finding:

Children exposed to violence since separation fare worse than those exposed only prior to separation (AIFS, 2020).

Ongoing instability creates more sustained risk than historical trauma alone.

Behavioral Manifestations

- • High levels of stress, anxiety, and fear (AIFS, 2020)

- • Social difficulties and peer relationship challenges (AIFS, 2020)

- • Aggression or violence mirroring home patterns (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025)

Culturally Diverse and Intersectional Vulnerability

Systemic Attendance Gaps

74.5%

ATSI attendance rate

vs 87.4% non-Indigenous (Clark, 2022)

19.7%

Very remote area attendance

vs 52.4% in cities (Clark, 2022)

Intersectionality of Risk

Family breakdown often precipitates socio-economic decline, intersecting with systemic disadvantage:

- • Family factors including parental health problems are known risk factors (Clark, 2022)

- • Community factors such as neighborhood poverty exacerbate school access issues (Clark, 2022)

- • Cultural sensitivity required in decision-making regarding religious and cultural upbringing (NSW Government, 2021)

The School's Obligation

Schools must prioritize the educational and welfare interests of the child above parental disputes (NSW Government, 2021), implementing proactive, trauma-informed responses that address both emotional needs and systemic barriers.

Our goal: Create predictable spaces where vulnerable students can heal first, then thrive.

From Reaction to Resilience

Whole-School & Classroom Interventions

The "Safe Haven" Imperative

The pervasive and complex nature of family breakdown (FB) and High-Conflict Divorce (HCD) demands that secondary schools move beyond reactive disciplinary measures. Instead, they must adopt proactive, trauma-informed teaching approaches to support vulnerable adolescents (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Neurobiological Impact

Chronic family conflict is not merely a social issue; it is a neurobiological stressor that compromises executive function and learning capacity (Orygen, 2025; Turpyn et al., 2017).

The School's Role

Therefore, the school must function as a consistent and secure "safe haven" for students whose home lives are defined by instability (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

I The Imperative for a Trauma-Informed Framework

The Physiological Reality

For adolescents experiencing HCD, the chronic, underlying stress—what teachers term an "all-encompassing underlying stress"—can lead to observable academic difficulties, including withdrawal, missed assessment deadlines, and poor concentration (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

"The adolescent brain is perpetually 'primed' to detect threats (Turpyn et al., 2017). This heightened state consumes regulatory resources required for complex academic tasks."

Beyond Standard Approaches

Standard pedagogical approaches often fail these students because they interpret these cognitive deficits as a lack of motivation or ability, rather than a physiological response to trauma (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019).

Interpreting withdrawal as defiance

Missing deadlines as laziness

Poor concentration as disinterest

The School as a Secure Environment

Teachers unanimously identify their primary role as creating a safe and secure environment where students feel comfortable to "be themselves" and "reach out" for support (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

When the home environment is characterized by "instability" and "constant unknown sadness," the school is tasked with providing predictability and security (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

💡 A strong, positive teacher-student relationship functions as a "gateway to mental health support" and resilience when students face adversity (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

II The Whole-School Framework: The Berry Street Education Model (BSEM)

To systemize the trauma-informed approach, the Berry Street Education Model (BSEM) offers a comprehensive framework grounded in both trauma-informed teaching and learning, and positive psychology (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019). The model specifically targets students who are often disengaged and disruptive, helping them develop the skills and relationships necessary to "heal first, then thrive" (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019).

| BSEM Domain | Core Focus | Trauma-Informed Goal for HCD |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Body | Physical regulation of stress response | Mitigating Chronic Stress: Teaches strategies to increase physical self-regulation and de-escalate heightened stress response (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019) |

| 2. Relationship | Nurturing on-task learning through relational classroom management | Restoring Trust and Safety: Fosters positive teacher-student relationships, offering stable attachment (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025; Bailey & Brunzell, 2019) |

| 3. Stamina | Cultivating academic persistence, resilience, and emotional intelligence | Countering Executive Function Deficits: Supports development of resilience to counteract emotional exhaustion (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025) |

| 4. Engagement | Motivating students with strategies to increase willingness to learn | Reversing Withdrawal and Disengagement: Provides strategies to motivate psychologically withdrawn students (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019; Podwinski & Laletas, 2025) |

| 5. Character | Harnessing a values and character strengths approach | Building Self-Efficacy: Instills self-knowledge for future pathways, enhancing diminished self-esteem (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019) |

Short-Term Outcomes

- Improved academic growth

- Enhanced social and emotional wellbeing

- Greater ability to maintain relationships

- Increased school attendance

Long-Term Outcomes

- Improved self-esteem

- Capacity for healthy relationships

- Reduced anti-social behaviors

- Improved Year 12 completion rates

III Classroom Implementation: Pedagogical Strategies and Reasonable Adjustments

While BSEM provides the conceptual blueprint, individual teachers must translate these principles into practical classroom strategies and Reasonable Adjustments (RAs), particularly for students whose emotional distress or neurobiological differences severely impede access to learning.

The Core Mandate: Reasonable Adjustments

The Australian Disability Standards for Education (DSE) mandates that schools must make reasonable adjustments—measures and actions designed to assist students with disability (including those with ASD/ADHD, who are high-risk) to participate in their learning on the same basis as their peers (Page et al., 2024).

Key Requirement: RAs must be the "product of consultation" and seek to balance the interests of all parties, including the student and their family (Page et al., 2024).

❌ Reactive Approach

Adjustments are made after a failure occurs (e.g., granting an extension after a deadline is missed).

Consequence: Reinforces the student's sense of failure; the associated anxiety is already triggered (Page et al., 2024).

✅ Proactive Approach

Adjustments are made before the need arises (e.g., providing duplicate materials at the start of the term).

Benefit: Reduces anticipatory anxiety associated with custody transitions, preserving cognitive resources for learning (Page et al., 2024).

Practical Reasonable Adjustments for Managing Logistical Stress

Duplicate Materials

Provide duplicate textbooks or ensure permanent digital licenses for all core learning resources to prevent anxiety during custody transitions (Page et al., 2024).

Flexible Assessment

Interpret missed deadlines as potential consequences of instability, not defiance. Implement flexible extensions through established IEPs (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Educational Welfare

In cases of high conflict, principals must make decisions based primarily on the best educational and welfare interests of the child (NSW Government, 2021).

Specialized Adjustments for ASD/ADHD Students

Students with ASD and ADHD depend heavily on predictable routines and structure. The unpredictability of separation exacerbates their anxiety and potential for sensory overload (Hetherington, 2017).

Visual Custody Mapping

Use interactive magnetic routine charts to map custody arrangements, providing destroyed predictability (Hetherington, 2017).

Functional Behavior Response

Understand that stimming behaviors serve functional purposes - attempts to regulate anxiety (Hetherington, 2017).

Retreat Space

Provide designated special places (quiet corner, tent, pod chair) for managing overwhelming emotions (Hetherington, 2017).

Teacher Aide Support

Teacher aides are crucial for successful RA implementation in mainstream classrooms (Page et al., 2024).

IV Overcoming Barriers: Cultivating Professional Competence and Empathy

The transition to effective trauma-informed support and consistent RA implementation faces significant barriers, primarily rooted in staff training and school culture (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Training Deficit

The most significant barrier reported by secondary teachers is a lack of formal or specific training in supporting students experiencing HCD/family breakdown (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

"Teachers report feeling that their learning occurs 'on the job' and that procedures are often 'informal' and 'very generalized'" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Lack of Empathy

Even when teachers are personally committed to pastoral care, their efforts can be undermined by unsupportive colleagues who lack empathy for students of HCD (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

"Staff who 'work with punitive practices, rather than positive support' focus on minor discipline instead of the student's heightened or depressed state" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

The Role of Leadership and Data

Effective implementation of RAs is significantly enabled when school leadership provides clear governance and promotes an inclusive culture. Principals play a pivotal role as instructional leaders and brokers of professional learning (Page et al., 2024).

Whole-School Training

Systemic implementation crucial

Compassionate Culture

Shared accountability

Proven Models

Focus on BSEM success

The Goal: Create a "Safe Haven"

—a predictable space free from the chaos of home.

By focusing resources on proven, trauma-informed models like BSEM and ensuring all staff are trained in both the legal and pedagogical necessity of proactive reasonable adjustments, schools can effectively mitigate the adverse effects of family breakdown and safeguard students' educational and emotional trajectories (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019; Page et al., 2024).

The "Demilitarized Zone"

Navigating Partnerships & Legal Boundaries

The School as Neutral Ground

Supporting students impacted by family breakdown (FB) and High-Conflict Divorce (HCD) requires secondary educators to walk a tightrope. They must manage complex, sensitive, and often adversarial parental relationships with professionalism, impartiality, and strict adherence to legal protocol (NSW Government, 2021).

To protect the student's wellbeing, the school environment must be preserved as a "demilitarized zone"—a safe and neutral space dedicated solely to the student's educational and welfare needs, rather than a venue for resolving parental disputes (NSW Government, 2021).

I Maintaining Neutrality: The School's Legal Position

The fundamental principle governing a school's actions in family law matters is the paramount consideration of the child's best educational and welfare interests (NSW Government, 2021). This mandate requires a strict policy of non-involvement in resolving disputes between separated parents.

The School is Not a Court

Educators and school staff must operate within clearly defined legal boundaries to protect both the student and the institution.

Non-Enforcement Role

It is not the role of the school to enforce Family Court orders. Schools are neither legally required nor equipped to interpret or police complex parenting orders (NSW Government, 2021).

Dispute Resolution

The school is not the appropriate place for family disputes to be resolved. When parents cannot agree, it is the role of the court, not the school, to determine those interests (NSW Government, 2021).

Impartiality

Any decisions made by the school must be unbiased and, as far as reasonably practicable, not favour either parent (NSW Government, 2021).

Parental Obligation to Provide Documentation

Parents bear the responsibility for informing the school about any changes in family circumstances that may affect the school-family relationship (NSW Government, 2021).

Court Orders: Parents are obligated to provide the school with copies of any court orders that impact the relationship between the family and the school (NSW Government, 2021).

While schools do not enforce these orders, they should be used by principals to ensure the educational and welfare interests of the student are properly addressed (NSW Government, 2021).

Security: These orders must be treated as sensitive and held securely (NSW Government, 2021).

II Legal Assumption of Shared Parental Responsibility

In the absence of any specific court orders stating otherwise, the Australian legal default is the assumption of shared and equal parental responsibility (NSW Government, 2021). This impacts which parents are entitled to access educational information and participate in school life.

Rights of the Non-Residential Parent

Unless a court order explicitly denies parental responsibility for education matters, the non-residential parent typically retains significant rights concerning the child's schooling (NSW Government, 2021).

Right to Information and Participation:

- Know the school where their child is enrolled

- Participate in school-related activities (parent-teacher interviews, events)

- Access documentation (reports, newsletters, test results)

Source: NSW Government (2021)

Crucial Boundaries for Information Release

The right to information about the child does not equate to the right to personal privacy information of the other parent. This boundary is non-negotiable.

Critical Boundary

Contact Details: Under no circumstances should the address or contact details of a child or a parent be given to the other parent without the first-mentioned parent's explicit consent (NSW Government, 2021).

Any school material provided to a non-residential parent must be carefully checked to ensure it does not include any address or other contact details of the other parent (NSW Government, 2021).

When Parental Responsibility is Removed

If a court order is made that denies parental responsibility for the long-term care of a child, or gives sole responsibility for educational matters to one parent, the other parent is not entitled to any documentation or information about the child from the school, subject to the specific terms of the court order (NSW Government, 2021).

III Managing Key Decisions and Disputes

Secondary schools must navigate complex decision-making processes for enrolment, name changes, and academic activities, always ensuring the student's voice and welfare are central.

Enrolment

Classified as a "major long-term issue" requiring joint consent unless court orders specify otherwise (NSW Government, 2021).

Safety Exception: If relocation is due to safety concerns, enrolment can proceed if in child's best educational interests (NSW Government, 2021).

Name Changes

Also regarded as a major long-term issue requiring joint consent. Students under 18 must generally be enrolled using birth certificate name (NSW Government, 2021).

Exceptions: Court order, both parents' consent, or safety reasons (e.g., witness protection) (NSW Government, 2021).

Permission Notes

Should generally be obtained from the parent the school usually contacts for day-to-day issues (NSW Government, 2021).

Disputes: Principal decides based on educational value, student interests, and student's views (NSW Government, 2021).

IV Managing Access, Pick-Ups, and Conflict on School Site

School access issues are often flashpoints for parental conflict, requiring staff to remain calm, neutral, and focused on maintaining safety.

Picking Up Children

- During School Hours: Parents should not be allowed to remove children before end of day unless pre-arranged medical appointment or exceptional circumstances (NSW Government, 2021).

- End of Day: A parent with parental responsibility can pick up children, absent a court order preventing them (NSW Government, 2021).

- Third-Party Collection: Parents can nominate another person (e.g., new partner) to collect the child on their behalf, even if other parent objects, unless restricted by court order (NSW Government, 2021).

Resolving On-Site Disputes

If both parents arrive and confrontation occurs, or is likely to occur, parents must be advised to resolve differences away from school site (NSW Government, 2021).

🚨 Police Involvement Required

If a parent refuses to leave, becomes aggressive, or uses/threatens physical violence, immediately contact police for child's welfare and staff safety. Staff are NOT expected to physically restrain parents (NSW Government, 2021).

V Dealing with Third Parties and Non-Parental Involvement

The involvement of individuals other than the legal parents (such as grandparents or step-parents) is entirely conditional upon the consent of the biological parent(s) (NSW Government, 2021).

Step-Parents and New Partners

Step-parents often play a significant role in a child's life, including involvement in school activities (NSW Government, 2021).

Involvement must be with express or implied consent of biological parent

Biological parent can withdraw consent at any time

Incidental contact during legitimate pickup is acceptable

Grandparents and Other Relatives

Grandparents and other close relatives generally do not have a formal relationship with the school and cannot interact with children while at school (NSW Government, 2021).

Information Requests: Requests for information (photos, reports) from grandparents should be politely declined without explicit parental consent.

Contact: Should generally take place outside school hours to maintain school as safe haven.

VI Critical Safety Protocols: Apprehended Violence Orders (AVOs)

Apprehended Violence Orders (AVOs) are made under criminal legislation and impose criminal sanctions if breached (NSW Government, 2021). The school must treat AVOs with the utmost seriousness, as they relate directly to safety.

AVOs vs. Family Law Orders

Situations can arise where both a Family Law Act order (parenting order) and an AVO are in place simultaneously.

Precedence Rule

If a Family Law Act order relating to time a child spends with a person is inconsistent with an AVO, the Family Law Act order will generally prevail (NSW Government, 2021). However, the principal should seek advice regarding any conflict issues (NSW Government, 2021).

Restriction of Access and Information

⚠️ Critical: When Child is Named as Protected Person

If the principal is aware of an AVO and the child is specifically named as a protected person, confirmation of enrolment must NOT be given to the defendant without express consent of the protected parent (NSW Government, 2021). This measure is taken because the parent may fear for their or the child's safety if the location is revealed (NSW Government, 2021).

VII Student Welfare and the Mature Minor

In all matters, the educational and welfare interests of the child are paramount. For adolescents, this includes recognizing their increasing capacity for autonomy (NSW Government, 2021).

Student Views and Maturity

While parents have parental responsibility until the child is 18, it is generally accepted that as children become older and more mature, they are more capable of making their own decisions (NSW Government, 2021).

Weight Given: In family law matters, the views of the child, particularly an older child, are generally taken into account by courts (NSW Government, 2021). Principals should consider the maturity of the student and assess their capacity to make reasonable decisions in their own best interest (NSW Government, 2021).

Privacy and Confidentiality

When a mature student objects to information being provided to a parent, the school must balance parental rights with privacy legislation.

Withholding Information: If a student objects, the principal may decide not to release confirmation of enrolment or reports if determined that doing so is not in the best interests of the child (e.g., due to history of violence or fear) (NSW Government, 2021).

The Teacher's Role in Referral

Although teachers must adhere to these strict legal and procedural boundaries, they hold a critical role as the first point of contact in identifying, referring, and emotionally supporting vulnerable children (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Recognizing Limitations

Teachers should recognize their limitations ("I'm not a psych") but embrace their instrumental role in connecting students with specialized supports (e.g., school psychologists or external agencies) (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Adolescent Demand

Young people of separated families explicitly request access to counsellors, psychologists, and support groups to help them cope with their situation (AIFS, 2020).

This underscores the importance of facilitating access to allied health professionals to address the high levels of stress and anxiety resulting from chronic interparental conflict (AIFS, 2020).

Critical Legal Reminder

"Teachers are not lawyers. Always refer complex custody documents and situations to the school leadership team. The student's educational and welfare interests must remain paramount in all decisions."

Bridging the Gap

External Resources and Crisis Support

The Imperative of External Referral

While secondary educators are often the "first responders" in identifying the signs of family breakdown (FB) and High-Conflict Divorce (HCD), the severity and complexity of the challenges involved often exceed the capacity and mandate of school-based personnel (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Chronic family adversity can manifest as neurobiological deficits, acute anxiety disorders, and complex legal safety concerns—issues that require specialized clinical and legal intervention (Clark, 2022; Turpyn et al., 2017).

This page serves as a comprehensive gateway, ensuring educators, students, and families can quickly access specialized external resources, reinforcing the school's position as a secure "safe haven" dedicated to student welfare (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

I Crisis Intervention and Immediate Safety

In situations where a student or staff member feels that safety is immediately compromised, or where concerns regarding family violence and abuse are present, immediate access to critical crisis services is paramount.

The Context of Risk

Family violence is a significant risk factor in family breakdown. Research confirms that parents who report experiencing physical violence or emotional abuse—whether before, during, or since separation—are more likely to report lower overall levels of child wellbeing and higher behavioral problems (AIFS, 2020).

⚠️ Critical Finding: Children exposed to violence since separation (post-separation conflict) fare even worse than those exposed only prior to separation, highlighting the critical need for ongoing safety planning (AIFS, 2020).

| Service | Contact Details | Purpose and Context |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency Services | 000 | For immediate safety concerns, or if worried about safety of self, another person, or a child (AIFS, 2020). Staff should immediately contact police if parent becomes aggressive or refuses to leave (NSW Government, 2021). |

| 1800 Respect | 1800 737 732 | National Sexual Assault Domestic Family Violence Counselling Service provides 24/7 confidential counseling for those experiencing domestic/family violence (AIFS, 2020). |

| Lifeline | 13 11 14 | Provides 24/7 general and crisis telephone counseling for anyone experiencing distress or suicidal thoughts (AIFS, 2020). |

Managing Apprehended Violence Orders (AVOs)

Breach Protocol

If school becomes aware of a breach, or if immediate concerns are held for safety of any person on site, police must be contacted (NSW Government, 2021).

Information Restriction

When child is named as protected person in AVO, confirmation of enrolment must be withheld from defendant parent to protect safety (NSW Government, 2021).

II Youth-Focused Mental Health Support

Adolescence is a neurobiologically vulnerable period characterized by significant stress and difficulty regulating emotional responses (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025). Chronic exposure to HCD leads to sustained cortisol secretion and compromises executive functions such as impulse control and emotional regulation (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Why External Support is Critical

Teachers play vital role in identifying internalizing symptoms (e.g., high anxiety, withdrawal) or externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression) (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

💡 Adolescent Demand

Adolescents themselves explicitly request access to "counsellors, psychologists, and support groups" to help them cope (AIFS, 2020). Connecting students to these specialized services is essential to address high levels of stress and anxiety from chronic interparental conflict (AIFS, 2020).

Kids Helpline

1800 551 800

Free, confidential telephone and online counseling for children and young people (aged 5–25) (AIFS, 2020).

Vital Resource: Essential for adolescents who commonly hide their need for support due to stigma (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Online Support

ReachOut

au.reachout.com - Online resources for coping with parental separation (AIFS, 2020).

Youth Beyond Blue

youthbeyondblue.com - Mental health support addressing stress/anxiety from family breakdown (AIFS, 2020).

Headspace

headspace.org.au - Early intervention mental health services for 12-25 year olds (Clark, 2022).

III Legal Guidance and Dispute Resolution

Family breakdown often involves complex legal and communication issues that the school is not mandated or equipped to resolve. The role of the school is to maintain neutrality and focus on educational welfare (NSW Government, 2021).

Addressing "Communication Uncertainty"

One of the largest barriers to providing support—particularly for students with Special Educational Needs (SEN)—is "communication uncertainty," where parents fail to collaborate on key decisions like Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

Clarifying Roles

External legal advice helps parents clarify their parental responsibility and legal obligations (NSW Government, 2021).

Enabling Adjustments

When parents utilize mediation services, they're better positioned to provide clear consent required for schools to implement necessary reasonable adjustments (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025).

| Service | Contact / Website | Key Areas of Assistance |

|---|---|---|

| Family Relationships Advice Line | 1800 050 321 | Information, advice, and referrals for family law issues, parenting arrangements, and separation (NSW Government, 2021). Primary referral for parents disputing major long-term issues like enrolment (AIFS, 2020). |

| Family Relationships Online | familyrelationships.gov.au | Government website offering range of information about family law and dispute resolution (AIFS, 2020). |

| Lawstuff (Youth Law Australia) | yla.org.au | Information and resources for young people about legal issues, empowering them with knowledge regarding their rights in separation process (AIFS, 2020). |

IV Addressing School Refusal and Specialized Needs

The interplay between family stress and pre-existing neurodevelopmental conditions (such as ASD/ADHD) is a major contributor to School Refusal, a specific type of problematic absenteeism characterized by intense emotional distress (Clark, 2022).

The Limits of School-Based Support

While schools can implement trauma-informed models like the Berry Street Education Model (BSEM), the specialized services needed to address underlying drivers of school refusal often fall outside the school's capacity.

Capacity Constraints

Australian schools frequently experience shortages of specialist knowledge and allied health services. Recommended ratios for school psychologists (e.g., 1:500) are often not met, necessitating reliance on external providers (Clark, 2022).

Complex Needs

For students with ASD, reliance on predictable routines means parental separation causes profound disruption. External specialists often required to design bespoke strategies, such as visual tools to map custody arrangements (Hetherington, 2017).

The Role of Socio-Economic Capital

It is essential to acknowledge that access to specialized support is often correlated with socio-economic status. Families with "greater social, cultural, [and] financial capital" tend to have more resources to manage school refusal and secure positive outcomes (Devenney & O'Toole, as cited in Clark, 2022).

🎯 Teacher Action: This reality underscores the immense importance of promoting accessible, government-funded resources (like Headspace and Kids Helpline) to ensure that all families, regardless of financial status, have a safety net (Clark, 2022).

V Professional Development for Educators

Secondary teachers often report a lack of formal training specific to trauma and High-Conflict Divorce, feeling that their learning occurs "on the job" (Podwinski & Laletas, 2025). Engaging with academic research and professional guidelines is a non-negotiable tool for continuous professional development.

Research & Theory

-

Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS)

Primary source for research-based information on family functioning and long-term effects of separation on child wellbeing (AIFS, 2020).

-

Berry Street Education Model (BSEM)

Resources on trauma-informed teaching providing theoretical grounding to implement strategies that focus on "healing first, then thriving" (Bailey & Brunzell, 2019).

Practical Resources

-

Raising Children Network

Evidence-based information on school refusal and supporting teenagers through separation (Clark, 2022).

-

International Network for School Attendance (INSA)

Resources and information on addressing school attendance problems globally (Clark, 2022).

By prioritizing access to these resources, educators can fill the knowledge gap, better understand neurobiological impacts (Turpyn et al., 2017), and effectively integrate specialized support into their practice.

🆘 Emergency Quick Reference

Life Threatening Emergency

000

Family Violence Support

1800 737 732

Kids & Youth Support

1800 551 800